Rising Waters, Erosion and Shoreline Management

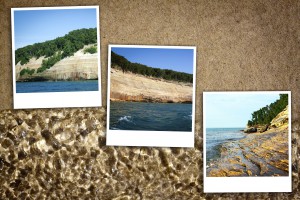

Without a doubt, boaters are always happy to see water levels rise on Lake Michigan, but high water levels mean nothing but trouble for lakefront home owners. With each episode of high lake levels, rates of bluff erosion increase, beachfront property is lost, and structures and beaches are submerged.

Without a doubt, boaters are always happy to see water levels rise on Lake Michigan, but high water levels mean nothing but trouble for lakefront home owners. With each episode of high lake levels, rates of bluff erosion increase, beachfront property is lost, and structures and beaches are submerged.

Evaporation, runoff, and precipitation over the lakes control the seasonal fluctuation of Great Lakes’ water levels. In recent decades, lake levels have been kept at relatively high levels. These higher than average levels typically peak once per decade and often cause considerable destruction. According to the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Lake Michigan water levels rose 3 feet from 2013 to 2014, followed by an all-time low in January 2013. From 2013 to 2015, the monthly average water level for Lake Michigan went from nearly 1-1/2 feet below the monthly average to 2/3 of a foot above the average level. Recent research by NOAA indicates that the water levels of Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, and Erie are expected to remain high into the fall of 2016.

Long stretches of Lake Michigan shorelines now have no visible beach and little nearshore sand regardless of season or lake levels. Great Lakes shorelines, including that of Lake Michigan, are now actively eroding even during periods of low water, in part due to the thinning veneer of sand on the lake’s floor, especially on the western coast. According to The Chicago Tribune, the amount of sand that flows south of Waukegan and protects the Illinois shoreline from pounding waves has dropped by an estimated 83 percent since the early 1800s, putting the coast at risk for more and more erosion. Without that thick layer of sand to serve as a cushion, incoming waves erode the clay lakebed itself. As the floor of the lake deepens, conditions for larger and stronger waves increase, hastening shoreline erosion. These more forceful waves threaten both public beaches and private shoreline property. While shoreline and lakebed erosion do occur naturally, pier and jetties interrupt the natural flow of sand along the lakebed and cause dunes to form on the north side of the structures, according to Charles Shabica, a civil engineer and retired Northeastern Illinois University professor.

Studies of Lake Michigan’s floor have found massive sand loss near the shore. In addition, the clay lakebed is eroding at an average rate of two inches per year along the Lake Michigan’s Illinois coastline. In areas like Lake Bluff, the erosion level is even greater. Shabica forecasts that waves will carve another three feet out of the lakebed over the next 20 years at a site where he plans to build a beach in Glencoe. Hydrologists from NOAA say waves normally break when their height reaches 80 percent of their depth, meaning, if Shabica’s prediction is correct, and the water level remains around its current level, a wave breaking at 10 feet today would be nearly three feet higher in 2035.

Studies of Lake Michigan’s floor have found massive sand loss near the shore. In addition, the clay lakebed is eroding at an average rate of two inches per year along the Lake Michigan’s Illinois coastline. In areas like Lake Bluff, the erosion level is even greater. Shabica forecasts that waves will carve another three feet out of the lakebed over the next 20 years at a site where he plans to build a beach in Glencoe. Hydrologists from NOAA say waves normally break when their height reaches 80 percent of their depth, meaning, if Shabica’s prediction is correct, and the water level remains around its current level, a wave breaking at 10 feet today would be nearly three feet higher in 2035.

Though an estimated 85 percent of Illinois’ Lake Michigan shoreline has some sort of protection, natural areas remain the most vulnerable and can recede at an average rate of 12 feet per year. One clear example of this vulnerability is Illinois Beach State Park. Its northern beach has lost more than 100 acres of coastal habitat over the past century and is expected to continue to erode by an acre each year.

Waukegan Harbor also presents challenges to shoreline preservation. Typically, sand along western Lake Michigan migrates from north to south, a littoral pattern that begins along the beaches of Wisconsin and ends at the Indiana Dunes. Yet much of this migrating sand gets trapped by the walls and structures of the harbor. Both Waukegan Harbor and the nearby Great Lakes Naval Station often block sand from reaching beaches south of the barriers. Public beaches immediately south of Waukegan in North Chicago and Lake Bluff are eroding as a result. Storms only make this situation worse. When superstorm Sandy hit the Chicago area in October, the tempest created 25-foot waves in Lake Michigan that carried nearly a year’s worth of sand accumulation into the approach channel of Waukegan Harbor. While many municipalities favor redistributing sand from the harbor to beaches suffering from erosion, permits and EPA testing for asbestos make this option cost-prohibitive. The truth of the matter is that nearby villages and towns cannot afford to pay for this solution.

Needless to say, there are many ways beachfront property owners can mitigate loss of shoreline. The trend now, according to Shabica, is toward building “pocket beaches,” which are protected with rock or steel piles on their fringes and a line of large headstones underwater that break waves farther from shore. Building pocket beaches essentially creates seawalls and rock revetments to protect your shoreline against erosion by displacing nearshore sand to offshore areas, a practice advocated by most environmental agencies.

Waukegan Harbor also presents challenges to shoreline preservation. Typically, sand along western Lake Michigan migrates from north to south, a littoral pattern that begins along the beaches of Wisconsin and ends at the Indiana Dunes. Yet much of this migrating sand gets trapped by the walls and structures of the harbor. Both Waukegan Harbor and the nearby Great Lakes Naval Station often block sand from reaching beaches south of the barriers. Public beaches immediately south of Waukegan in North Chicago and Lake Bluff are eroding as a result. Storms only make this situation worse. When superstorm Sandy hit the Chicago area in October, the tempest created 25-foot waves in Lake Michigan that carried nearly a year’s worth of sand accumulation into the approach channel of Waukegan Harbor. While many municipalities favor redistributing sand from the harbor to beaches suffering from erosion, permits and EPA testing for asbestos make this option cost-prohibitive. The truth of the matter is that nearby villages and towns cannot afford to pay for this solution.

Needless to say, there are many ways beachfront property owners can mitigate loss of shoreline. The trend now, according to Shabica, is toward building “pocket beaches,” which are protected with rock or steel piles on their fringes and a line of large headstones underwater that break waves farther from shore. Building pocket beaches essentially creates seawalls and rock revetments to protect your shoreline against erosion by displacing nearshore sand to offshore areas, a practice advocated by most environmental agencies.

The condition of steep slopes or bluffs along the shore also affects beach quality and plays a key role in shoreline stability, especially during times of high water levels and increased storm activity. High waves can erode soil at the bottom of the bluff, while groundwater and water from gutters pose a threat from above. Erosion of these higher shoreline areas can be avoided by retaining moisture-absorbing vegetation on the bluff, configuring rain gutters to divert surface runoff away from the bluff, reducing the runoff rate and ground water flow toward the bluff, minimizing paved areas, and avoiding building heavy structures on the bluff edge.

The condition of steep slopes or bluffs along the shore also affects beach quality and plays a key role in shoreline stability, especially during times of high water levels and increased storm activity. High waves can erode soil at the bottom of the bluff, while groundwater and water from gutters pose a threat from above. Erosion of these higher shoreline areas can be avoided by retaining moisture-absorbing vegetation on the bluff, configuring rain gutters to divert surface runoff away from the bluff, reducing the runoff rate and ground water flow toward the bluff, minimizing paved areas, and avoiding building heavy structures on the bluff edge.

Find out how The Beach Comber can help you develop a plan protect your property today so you can your beach for years to come.